A curious thing happens when you are criminalised. You find yourself living in a state of hyper visibility, while simultaneously being entirely invisible. A curious duality of existence, suspended in a reality of being unseen and seen, navigating a new reality while longing for real freedom, the kind you feel in the belly of your muscles. As you walk through spaces, surveying the landscape that you now find yourself in, you come to understand that you are changed. Prison changed you. It changed you on a molecular level. It altered your dialogical relationship with the state and with everyone around you. It altered the way people interact with you, the way you are perceived, and it shifted the goal posts on you – in fact, the goal posts became these ever moving, floating poles, flapping around in the sky. You never seem to be able to reach the touch line, never seem to score a goal, never seem to find the finish line. You aren’t meant to. You aren’t a winner, nor will you ever be again. You are now one of this country’s disposable humans. Maybe you always were, either way, it doesn’t matter anymore, that’s all history. You are now an outcast cast out, and you have to find your home on the margins, a place devoid of warmth or opportunity, instead cold shoulders and closed doors. But you learn to make a life here, or at least you try to.

I thought I knew a lot about life before I went to prison. I hadn’t led a sheltered existence, I had seen things, done things, experienced joy and sadness, grief and pain, loss and love. One of the most significant things that shaped my early years, was my mother being killed when I was a baby. I honestly believe that was the point of radical departure in my life. I think her death, rather than her life, altered the trajectory of my life course. I think losing her, losing someone I cannot even remember has affected every single relationship I have ever had, and impacted every single choice I have ever made. But going to prison, made me infinitely wiser. I learnt so much about human behaviour, about violence, about men, and mostly about power. I was quiet inside. I watched people. I watched the screws, mainly. I watched them with each other, and the way they interacted with the women. I surveilled and classified them. It was partly an attempt to keep me safe from their predation and harm, but also to study them. To study power in its rawest, most primitive form. I wanted to understand how these beasts operate, so I could take them down, rip them apart and annihilate the system they serve.

All of that studying honed my people reading skills. I became so fucking sharp, I could spot a predator at 5 paces, and detect bullshit like a finely tuned lie detector. Even more so, when I came home, I found that my tolerance for bullshit was really low, almost non-existent – although admittedly this didn’t translate to my intimate relationships (I landed myself a pretty crappy marriage), but professionally, I could not tolerate wasters, and similarly I would not tolerate the actions of the state. It meant I behaved like a human sorter, sifting through people and situations, avoiding and discarding what I could not tolerate or what was not good for me, and gathering in close what or who was revolutionary, freedom focussed or embodied some form of radical love. I held a truth, my truth, and guarded it in my rib cage, nestled next to my crimson heart, a heart that beat only for liberation. It was and remains my only focus. I could care less for platforms or personal gain, I care about freedom – my own, and the freedom of every single person I left behind, and all the people that came after me. To this end, I determined I would consistently walk tall, speak honestly and firmly, and always from the chest, run straight, and always walk through the front door.

But I am a criminal – or at least that is the branding the state and the media have given me. And criminals don’t get too much grace when we speak out or speak up. In fact, when we speak up or even ask a question, or raise an eyebrow or God forbid our voice, we are seen as the threatening, violent types, the delinquents, the spooks beneath your bed. I experience it often because I am someone who questions and queries and challenges. I am a curious storyteller; I’ve always asked a lot of questions. And I am an activist, I have always challenged the status quo.

So, this week, the very first week in the new year, I have found myself embroiled in some kind of back and forth with a group of formerly incarcerated people about an Australian chapter of the Global Freedom Scholars (GFS). The back and forth that we were engaged in, I understood to be a professional exchange of ideas and contemplations, because (a) we are all adults, (b) my comment, post and email was professional and not at all personal and (c) the post I shared with my comment was already publicly available. However, as these things usually go, my questions, queries and challenging was not received in the spirit within which it was intended and while I was initially invited to meet with the chapter lead, what followed was an accusation of aggression and abuse. I was quickly (and typically) cast as the aggressor, as an angry woman exacting violence on the members of the chapter who, aside from one who contacted me privately, seemingly felt deserving of their positions and above reproach or even simple inquiry.

At first, my instinct was to internalise their response. I am a chronic self-reflector, so it’s a natural reflex of mine. I felt the familiar pangs of guilt - the kind my parole officer used to elicit from me, or the way my ex-husband used to gaslight me into feeling. However, after I had taken a moment, re-read my post and my email a few hundred times, I reminded myself that people’s responses are actually a reflection of how they feel about themselves and their actions rather than a reflection of mine or of what I wrote. I felt comfortable with my words, with my assertions and with the tone I set for my queries. I was not rude, I was not derogatory, in fact, I felt I was at peak professional, compared to how I felt in the base of my belly.

So, this brings me back to being seen and unseen, and the duality I find myself existing within, and how it feels to navigate a space like the one with the GFS. In this scenario, I was actually raising my concerns about the systematic invisabalising of those who had gone before us in this movement, and what I perceived to be the collective erasure of decades of work that pre-dated people like me. Labour done predominately by women, who forged pathways for people like myself to enter the knowledge industry. It was as if those lighthouses had never even existed. The Australian chapter of the GFS in its inception and by its own design, either intentionally or unintentionally (I had not made an assertion either way), was making the trailblazers of our own community unseen. This very action is the work of the carceral state.

We do not do this to each other – and we especially do not do this if we are freedom focussed.

No matter our differences – our viewpoints, politics, or positions on any agenda – as prisoners, we are not each other’s enemies. Our fight is always against the system and its

agents who oppress us, not against one another. We must always punch up, never at our fellow prisoner, because solidarity is our strength. But solidarity doesn’t mean silence. It doesn’t mean we can’t challenge each other, or ask hard questions, or call for new agendas and different ways of doing or being. Because growth and change come from these conversations, but they must come with respect and recognition of our shared struggle. No sliding into someone’s DMs with a sly message accusing them of abuse, when you could have just emailed them in the email train you were a part of. No joining in the pile on of vigilante-style social media posts just because you’re happy to see someone ‘get their day’. No expecting to act on behalf of our community without being held accountable for your actions.

If you position yourself as a representative of our community or as a leader, you must lead. To lead, means you will face challenges from within our community. It means acknowledging that sometimes we won’t agree, that’s life, and it’s healthy – but when we disagree, we can spar out our differences with integrity and respect. That’s how we build something stronger together.

That is how we pave a path to liberation for everyone, not just the select few that are deemed worthy.

Not just the select few that are visible or seen.

Personally, I've been an activist since I was 12 years old. I've always been hard-line, principled, and idealistic. Some have seen that as a weakness, but I’ve come to know it’s one of my greatest strengths. I share all this today because I believe in transparency in this movement, but also because I can spot bullshit at five paces. I can read people, and I know how to protect myself and those I care about.

When I came out of prison, I started speaking loudly about what I’d seen inside—what happened to me and what I witnessed. Many times, speaking out came at a great personal cost to my liberty. Watching on with worry, my dad would say, ‘Wait until you’re free of the system before you speak up.’ I’d reply, ‘Dad, they won’t be able to disappear me quietly into the night if I’m highly visible.’

That is the energy I’m bringing to this matter. I will be visible. Because for me, visibility oftentimes equals safety—not always, but my gut tells me this is one of those times to be unapologetically visible and radically transparent.

I just didn’t think I would need to don a high vis vest in this scenario, with this group of people.

I guess it’s a timely reminder for our community that we must always be mindful that liberation demands that we remember who we are fighting for and what we are fighting against. It demands that we hold each other accountable, yes, but that we also hold each other up. It demands that we remain focused on the system that oppresses us and refuse to let that same system influence the way we treat one another.

We are not here to replicate the state’s harm within our own movements. We are here to dismantle the damn system. To refuse invisibility for anyone, to ensure that no one’s labour is erased, and to make clear that no one is disposable.

The road to freedom isn’t easy, and it isn’t always smooth. But it must always be honest. It must be principled. And it must be built on radical love and respect. That is how we create a path forward. That is how we truly fight for freedom.

That is how we will free us all.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In the spirit of transparency, and in the making seen what may have been unseen, here are my contributions to the Australian GFS matter:

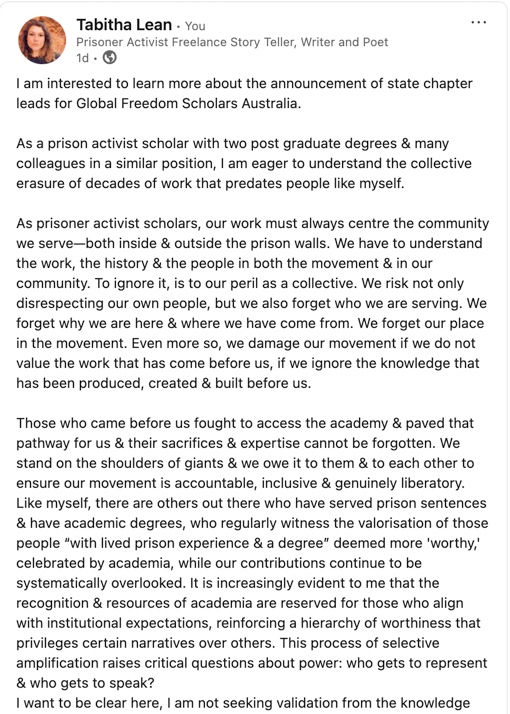

My initial comment on the announcement of the Australian Chapter of the GFS:

My post (which included a re-share of the Australian GFS public post announcing the state and territory leads):

My email responding to an email from Dwayne (The Australian organiser of the GFS):